Unless otherwise noted all pictures and text are by and copyright 2004 Mike Strong

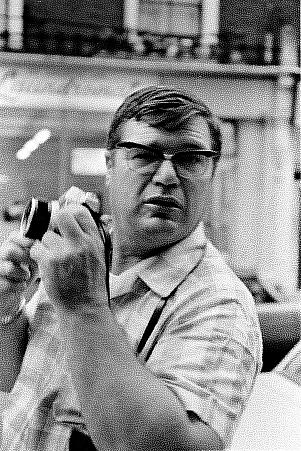

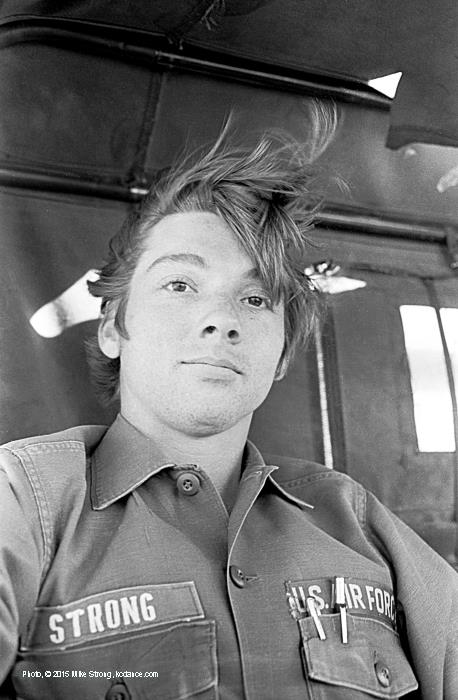

Riding in a deuce and a half in the Southern California desert, El Centro area, Jan/Feb 1970. I am holding the camera with my right hand on the door. |

Mike StrongPhoto CVThe Air Force - 1968-1972 |

1969 and Four Years in the Air Force

Nothing like being color blind to keep you from a job you do well. I painted as a kid so being color blind was not a condition I suspected. The term "color blind" is a poor description. Color blindness comes in a spectrum of severities and color sensitivities. Most persons are only a little blind to colors. In my case it is a lesser sensitivity to red and green. Almost no one on the planet is actually unable to see color. My grandfather could confuse reds and browns. For me, much subtler shifts are not noticed although I will often see them when someone calls my attention to them. I can actually work in a color photo lab and get relatively close but I could never be a color caller (quality-control person in a color lab). I've known people who saw color with the same definitiveness as some persons have perfect pitch. For me, subtle changes in red or green can go undetected.

I was always very good with black and white in the darkroom but Photoshop totally frees me with color. I've used Photoshop since version 2.5 about 1992. The ablility to see a digital readout of colors makes it possible for me to do good color corrections on an image. The other part about good color is that all the colors seem to come alive as the balance corrects. The deader the colors the more the balance is off, normally. Having a known black, gray and/or white (neutral colors) in a scene gives me a target to correct. In addition, skin tones have a characteristic RGB pattern (regardless of skin color) which I can use to good advantage by looking for the pattern and then checking the aliveness of the colors as I adjust the pattern shape with control sliders, even when I can't discern the subtler corrections as specific color tints.

I didn't become a photographer in the Air Force. They require perfect color vision. Instead I was sent into an occupation which supported photo-mapping, geodetic computing and geodetic surveying. For tech school the Air Force sent us to the Army's TopoCom engineering school at Ft.Belvoir, Virginia, just outside Washington, DC. My first day in class we were handed phone-book sized books filled with numbers and formulae. I said, they must have the wrong guy, all this math. Well, they said, we always have other jobs if you flunk out here. Only one person flunked that class. There were some 20+ of us in the class, 16 or 17 were Air Force, 3 marines including a gunney and a lance corporal, 2 army (spec 4 and a sergeant) and 1 navy.

|

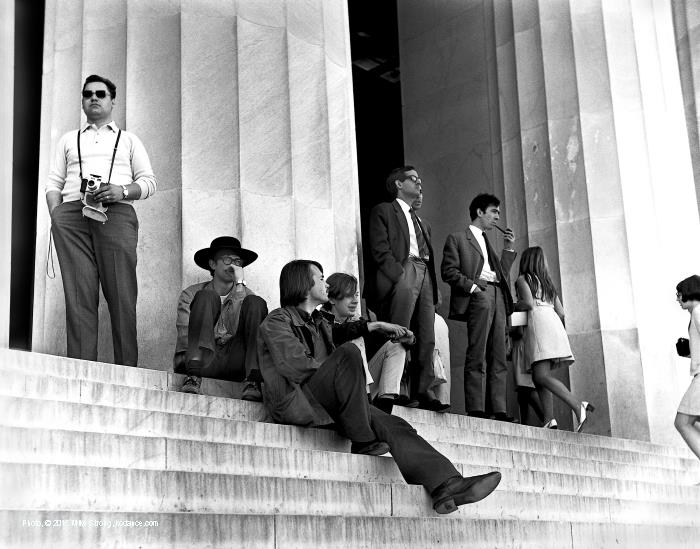

The Lincoln Memorial, early 1969. Honest to goodness hippies of the period, tourists and pipe-smoking office types on lunch break. |

|

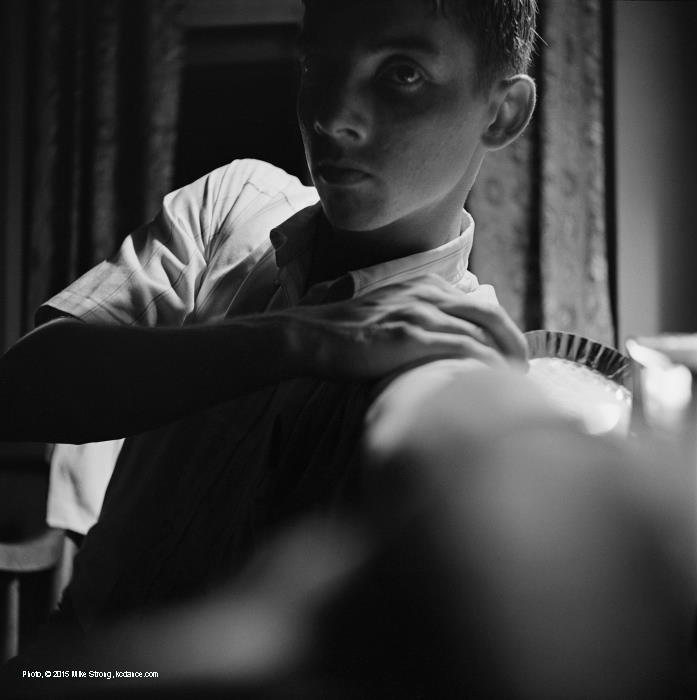

Me, early 1969, on weekend pass, in New York City, staying at the YMCA. I shot pictures and visited the small shop from which I had earlier purchased my Nikon via mail order. |

|

At the capitol - on a weekend from tech training at Ft. Belvoir, VA. |

I've always considered that landing in a math-based job in the Air Force was a life irony after having such a bad time of math in the university. One of those little jokes of fate. In the Air Force I learned that job, I was good in it, it was my work. Karma, maybe.

Most of the Air Force in the class went to Keesler AFB in Louisiana for further training in Combat Skyspot (link1-milwiki, Wikipedia, Battle of LS-85 [before me])and assignment to South East Asia. My orders sent me to Cheyenne Wyoming and F.E. Warren AFB. There I reported to the 1st Geodetic Survey Squadron. (history link1, )

The job was a "TDY" job - Temporary DutY. We would be assigned to a job for a few days to months at a time. When we came back we spent some time in the office and then were sent out again. It was hard on the married guys. I loved it. I got to travel all the time. When we sent equipment we would usually load our items on a pallet or three or more and ship it on cargo aircraft with a courier along to assure that it got there. I loved the courier duty to and from the job because I loved being on airplanes. I had worked as a lineboy at my local airport and there was all that time in the Civil Air Patrol. So I rode airplanes, in the cockpit, every chance I got.

|

This is a Wild T-4 Theodolite, made in Switzerland (Wild is pronounced "vildt"). It is a "broken telescope," which means that the light path breaks at right angles into the eyepiece (on the right in this picture) rather than continuing straight through. The T-4 was first produced in 1944 and stayed in production for four decades. I spent most of the last 1/3 of my Air Force time staring at stars with this instrument. It was used to determine first-order class one astronomic positions (latitude and longitude). It comes in two large pieces, the yoke on the bottom and the telescope on the top. When put together it is probably three feet tall or so. In operation, stars, a bit dimmer than what you can see with the naked eye, are followed by the operator delicately turning a wheel to place and then keep a crosshair in the exact center of each star as the star moves across the observer's meridian. At the same time electrical contacts on a small drum create tic marks on a roll of paper on which a separate chronometer is making another set of tic marks. Several dozen stars are observed each night for several nights and the results are meaned. |

For any job not on a military base we sometimes wore civies. And we had money. That job paid us per-diem. Un-taxed expense money, at a day rate. My best per-diem was in London but we also had survey crews in remote places from Pitcairn Island, to the Seychelles, to Brazilia, Curacao and other great spots. My TDY were all over the US except for the southeast and all over England (only, not Scotland, Wales or Ireland).

For any job not on a military base we sometimes wore civies. And we had money. That job paid us per-diem. Un-taxed expense money, at a day rate. My best per-diem was in London but we also had survey crews in remote places from Pitcairn Island, to the Seychelles, to Brazilia, Curacao and other great spots. My TDY were all over the US except for the southeast and all over England (only, not Scotland, Wales or Ireland).

Even southeast asia was highly desired and hard to get. Renting a house to operate out of, even hiring a housekeeper, getting per-diem and a chance to buy all kinds of great stereo gear at incredible prices.

Our squadron was marked by muscle cars in the parking lot and the most modern stereo gear in the barracks rooms. It was more like a college dorm for spoiled rich kids. There were no morning formations to report to. We could ship back our aquisitions right along with our regular survey equipment. Here are a couple of our guys unloading stereo gear from a pickup after a job in Thailand. Thailand was a six-months-at-a-time TDY.

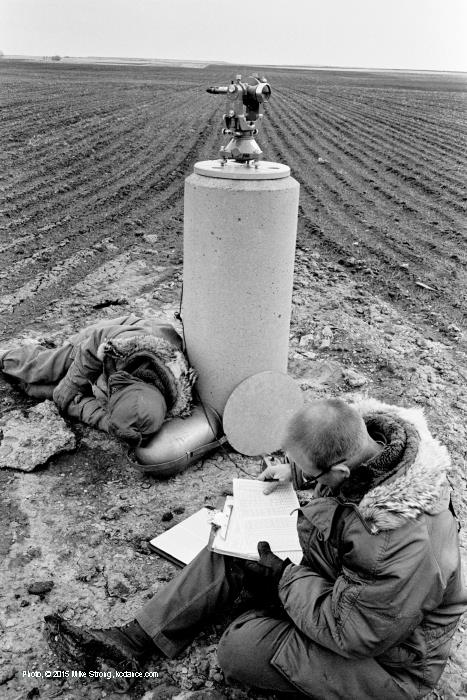

Doing levels in the Salton Sea area around El Centro, California. This area is below sea level. It is also called the American Sahara because of its resemblance. Movies such as "Sahara" with Humphrey Bogart were shot in this area. The sand dunes are enourmous and get a lot of dune-buggy week-enders from Los Angeles. Jim Drivas labeled our deuce-and-a-half military truck a dune buggy because it could pull with all wheels and would drive over anything.

On this job we were putting lattitudes, longitudes, elevation and azimuths on various cine-theodolites on the Navy's parachute test range where the Navy tested parachute operations for all sorts of uses including space capsules. They photographed descending equipment using cine-theodolites. These are movie cameras which record azimuths and elevations in the movie frame. |

|

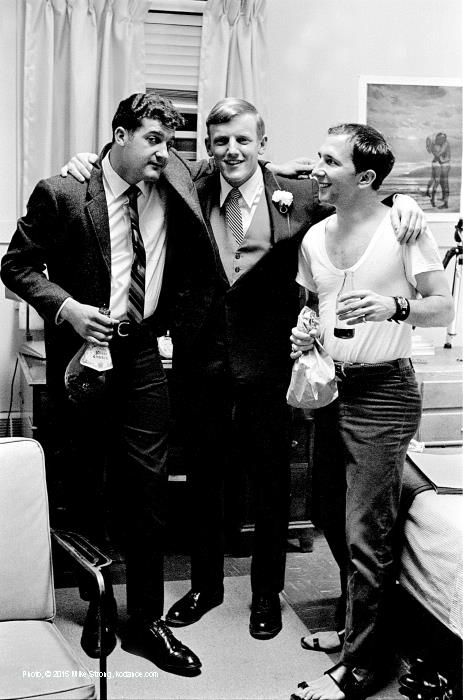

Here, in the barracks, are three of our rowdier, properly shameless members of the squadron. Probably about '70 or '71. This looks like the start to a night out because no one looks too far gone yet. Left to right: Jim Drivas (Schnectady, NY), "Red" (Bill) Crawford (Boston, MA), Bob Tripiciano (Auburn, NY). Red is now deceased. Bob got out before I did. He was a photographer and a trumpet player. Later we shared an apartment in Auburn, NY. Bob died a few years ago in Phoenix, AZ. Jim lives in Florida. |

|

This was taken in a DC-3 on a trip to West Virginia. In this case the Air National Guard flew a team of us and our equipment to West Virginia for a job in Greenbank. We put positions (latitude, longitude, elevation) on a couple of radio telescopes. It darn near turned bad as the pilot followed a VORTAC to find the airport. We could see mountains with trees well above our flight path. They turned around and flew us back to Wright field at Columbus, Ohio where we spent a night waiting for the next day and clearer conditions. The flight nurse, seen in the doorway sipping coffee was along to fill in his monthly time-in-air hours requirement. He was on headphones when the pilots realized they were flying blind at less than mountain top heights. When they turned around he came back amused to tell us what had happened. In the right foreground you can see the top of the fiberglass packing crates we used for almost all of our equipment. The next year one of these Gooney Birds crashed fatally in Cheyenne. I don't remember whether it was the same pilot and/or the same aircraft. |

Here are hazards of the job. No, the guy lying on the ground is not dead or wounded, just trying to get a few winks of sleep after a night of observing azimuths on missle sites. Sam is being the observer, making the measurements. The other guy (close to the camera) is the recorder, taking down the measurements and calculating them. This is in South Dakota, somewhere east of the Black Hills in a farmer's field next to a Minuteman missle silo. The instrument on the pylon (the concrete pillar in the field) is a Wild T3 with which we shot most of our angles (called directions) and azimuths (an angle measured clockwise from north). Each Minuteman missle site had two of these pylons about 300 meters or so from the "A-point," a survey marker embedded in the missle silo itself. They were used as a mathematical base for aiming missles, a sort of mathematical gunsite, if you will. Our measurements established where they were and where rotational north was related to the pylons and the A point. After we did our bit the targeting teams would use our data to turn angles into the missle directly in order to aim the missle. The pylons were made of epoxy-concrete and penetrated the ground some 16 feet - where they belled out for stability. They still moved all the time. Partly from the ground (always moving a few millimeters) and sometimes as tractors bashed against them. On top was a permanently mounted, thick, circular, aluminum, forced-centering theodolite mount (had three machined v-grooves radiating from the center at 120-degrees from each other). In the picture, you can see the trivet bottom points placed in the grooves which made sure the instrument was always centered. At night on the sights we would shoot azimuths from the A-point on the site (marked by a survey marker [small metal disk with a punched indentation in the center which was its location]). During the day we would shoot directions to re-establish or confirm the pylon positions. If the pylons moved even a little they could send the missle way off target. This method changed after geosensors were introduced. These were hatbox sized and shaped blue containers which carried very precise gyroscopes. The gyros were accurate enough to determine true north to navigational specifications. A first-surface mirror on the side of the geosensor allowed targeting teams at the missle to use the device as the aiming point rather than needing to see the pylons in the fields. The first one I saw was in spring 1971 at Kirtland AFB, Albuquerque, New Mexico, where we were doing a survey for tiltables for the C5's there - for their gyro compasses used in their inertial navigation systems. It was still experimental and a guy working on the device told us this would replace our annual missile site updates. I really pooh poohed that idea. Then in August 1972, I was sent to Whiteman AFB in the middle of Missouri, on the first team to certify the geosensor. That was also the last time I derided a promised engineering development. |

|

|

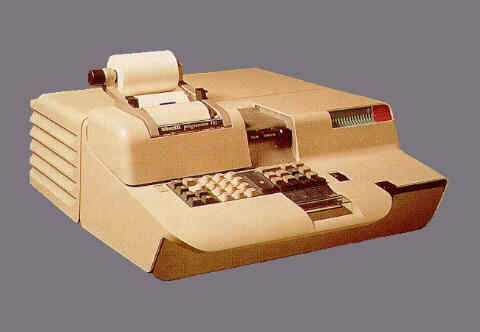

The Ollivetti P-101 Programma - This was a programmable calculator. We used it in the field (i.e. hotel/motel rooms) as a portable computer to run through our calculations. It was one of the first portable computers. It took all of 128 machine instructions on a magnetic card which slide down a path in the front center - where you see the cut-in area. Cost was several thousand. It weighed, I think, about 50 or maybe 80 pounds. It was metal, built like a Panzer and about two-feet by two-feet square. I still have a book of programs for this machine, a good number of which I wrote and which were published in the squadron for other teams. Input was the numeric keypad. Output on the P-101 was on the cash-register type paper roll. Long programs were handled by dividing the program into sets of 128-instructions at a time and chaining them together (loading the first part and running it, then the next part and so on - the register values from the calculations remained as the next part of the program was loaded). Chaining methods were used by a lot of machines in those days. This grew into overlays and DLL's. I think we first used the Ollivetti in 1970. The portable computer which followed this was a Wang with a Nixie Tube readout, a cassette tape for programs and an IBM Selectric Typewriter for output. That was coming into the squadron in 1972, the year I got out. |

Gallery - on the Job

I loved this job because I got to drive on the "wrong" side of the road, got to shift gears like crazy (small cars, small engines and lots of gears) and could walk down the streets of the big city and hear languages I didn't begin to understand (at first that included the British). |

Al Billups - everybody liked working for Al. |

Charley Middleton. A social worker from Charleston, SC, Charley worked in the squadron. He had everyone figured and by and by we realized he was right. |

Sgt Ackley turning directions with a Wild T-3 in West Virginia. This job was at Greenbanks, West Virginia radio astronomy observatory. Our job was to put positions on a 180-foot equatorial dish antenna. It was the first time we used a laser Geodimeter to measure distance. Measuring distance with lasers was new at the time. |

TSgt Abrams on a level in the desert in Southern California, on the parachute test area job around the Salton Sea. |

Cowboy at the Cheyenne Frontier Days rodeo. I got a spot in a trench dug in the ground in the middle of the arena for photographers. This was shot with a 300-mm Novoflex follow focus lens that I really loved. Long gone now. |

Cheyenne Frontier Days - Quarter-horses racing. 300-mm Novoflex from the rail. |

Gallery - London, England, 1971

In 1971 I was on a job (TDY) to England. We were sent to do a survey for microwave-tower placement. This was because de Gaulle had chased us out of France a few years early. The microwave towers transmit telephone conversations and they were part of the communications grid.

Taking my passport picture in 1971. Rank here is E-4. I became an E-5 a few months later. |

|

Hyde Park outside our first hotel in London. Art in the park. |

|

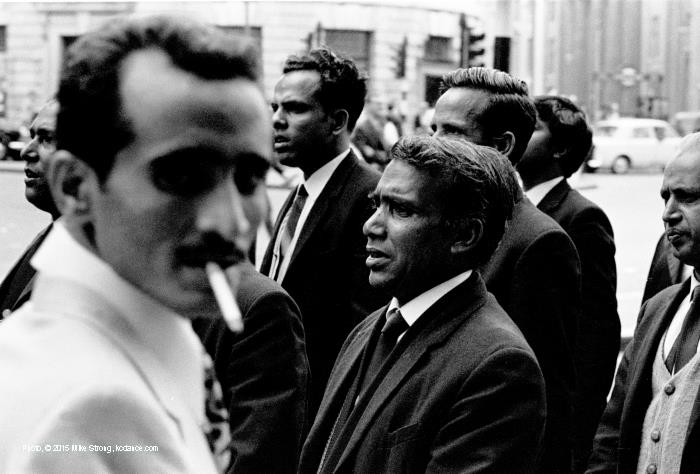

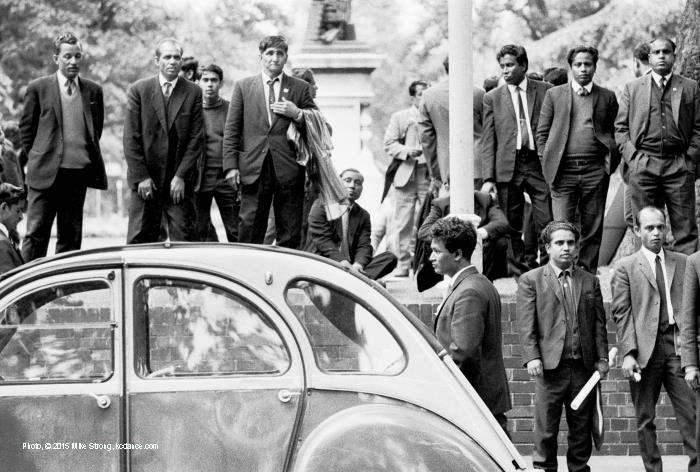

Here is a 1971 demonstration by Bengali's in the middle of London to free Sheikh Mujib from prison in Bangladesh. I remember the demonstrators were all very orderly and the cops (those famous London Bobbies) escorted them rather than putting up an opposition line. |

|

For a densly populated area, England has a lot of greenage. Forest views like this seemed to be many places. We spent a lot of time in fields and on hills although there were also many buildings with survey points on their roofs. |

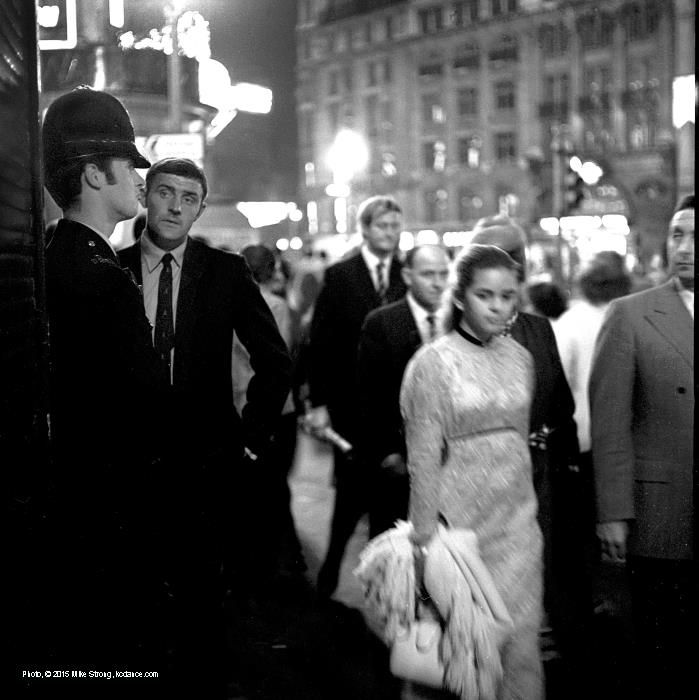

I don't know why this man is staring at the Bobbie. We had our weekends free and would commonly head downtown using the tube (subway). This is a typical Saturday night crowd. |

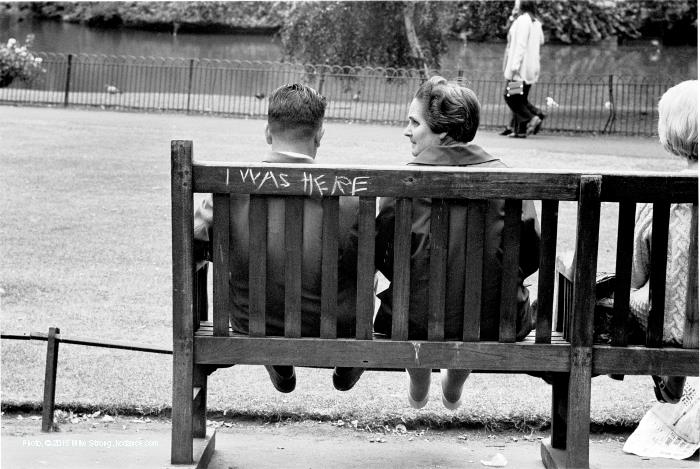

London is filled with great parks. Everyone came by, including the person who wrote "I was here" on the back of this park bench. |

|

|

We stayed in an Irish guest house with a little pub on the lower floor. It was very congenial with a lot of travelers from Dublin.They even sang songs, with good baritone voices. |

||